For the past three years, Dr. Andrea Zorbas has worked at the San Francisco Stress and Anxiety Center located South-of-Market, providing psychological counseling for adults. According to Zorbas, her clients, who often come with “career-related” worries, “all have an undergraduate degree, and most have a postgraduate degree,” and largely work in the tech industry.

Before moving to private practice, however, Zorbas spent a decade treating adolescents from low-income neighborhoods around the Bay Area, including two years at the KIPP Bayview Academy, a charter school for grades five through eight with a 48 percent African-American student population. She simultaneously managed a caseload of Bayview teenagers on probation for Urban Services YMCA. Among her patients, she recalled “high anxiety, high levels of depression and hopelessness,” and, frequently, post-traumatic stress disorder, owing to “the continual community violence that was happening, whether that was families being robbed or gun violence.” She found girls especially vulnerable, searching for “safety and security” that was sometimes impossible to find.

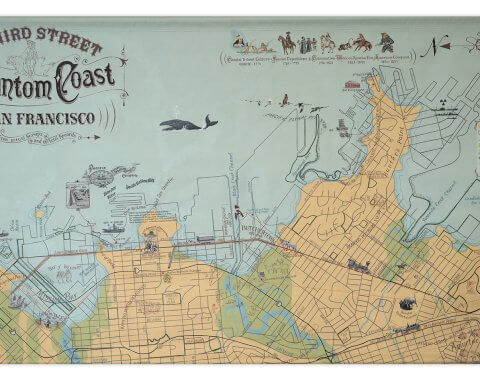

Zorbas’s patient population faced “all the standard challenges of low-income families,” trials that were amplified as San Francisco’s cost of living steadily increased. “Often families in the Bayview have been there for generations; people often know each other. And now the Bayview is starting to be gentrified, so families are then starting to get kicked out,” she said. “The disparity in the City is so extreme. Here we have these new tech guys moving into the Bayview, like 24-year-olds making hundreds of thousands of dollars, and then you have generations of families there just scraping by, and it’s this really odd dichotomy. My kids were already facing a lot of different levels of oppression,” but the presence of these newcomers “threw it in their face a little bit.”

As the neighborhood changed, a new type of anxiety emerged among Zorbas’s teenagers, revolving around a fear of gentrification and displacement. “When you grow up in an unsafe environment, you become hypervigilant about what’s going on in the community, so when you see a dilapidated house next door getting sold for a couple million dollars, you’re thinking, ‘OK, when is my landlord going to kick us out so they can do the exact same thing?’” she posited. “You’re just on edge. Are you going to be able to stay in San Francisco? Are you going to be homeless? That was absolutely on their minds. They get anxious about it because their parents are anxious about it.”

When she was hired by the San Francisco Stress and Anxiety Center, Zorbas, knowing her clientele’s demographics, anticipated a job that “could not be more opposite of what I used to do.” But her new clients simply represented the opposite side of the same coin. Here, again, she was dealing with the insecurities brought on by San Francisco’s new tech culture. Many of her clients were young women whose hypercompetitive workplaces had eroded their self-confidence. Despite having good jobs, they worried about money, living “check to check” in order to pay their expensive rent.

Though often transplants, they too wondered how long they’d be able to afford to live in the City, and what’d happen if they got fired. “Even if they don’t like a job, they have to stay in it because they want to stay in San Francisco. It’s like: ‘I came here for this opportunity; I’ve got to figure out how to make this work.’ And then, at work, every project is that much more pressure, every presentation, everything, because they’re hanging on by a thread, and they don’t want to go back to Ohio or wherever.”

In 2015, a The Atlantic article, “The Silicon Valley Suicides,” detailed journalist Hanna Rosen’s investigation into “elite American adolescents whose self-worth is tied to their achievements and who see themselves as catastrophically flawed if they don’t meet the highest standards of success.” Stressed-out high schoolers had thrown themselves in front of Caltrains in Palo Alto. Now, parents and mental health experts worry that, as Silicon Valley’s ethos envelops the rest of the Bay Area, similar challenges have arrived in San Francisco, where the industrious habits of the perpetually busy, ambitious professionals who increasingly populate the City are trickling down to their more fragile children.

The passing Caltrain is audible outside the office of Potrero Hill Psychotherapy, where Dr. Jocelyn Cremer meets with teenagers who tend to experience “a lot of anxiety about high school and grades and pressure to perform and what are they going to do for their life.” Cremer noted that she’s “seen an uptick in anxiety in the 20 years I’ve been in practice.”

Teenagers today “definitely have way more homework than I had, and they definitely get less sleep than I did,” according to Cremer. The adolescent lifestyle in San Francisco seems to mirror that of the City’s adults. “People don’t work 40 hours a week and then come home and have a cocktail like a Mad Men episode. People are working 50, 60, 70 hours a week; people are emailing their boss on Sunday.”

Rosen largely blamed the demands and expectations of affluent, success-oriented Palo Alto mothers and fathers for their children’s distress. Cremer doesn’t perceive the same crisis of parental values in her clients. Rather, she sees kids and grown ups equally as victims of a culture that’s become self-perpetuating. “I have teenage girls who have parents who don’t want them to get straight A’s and don’t put lots of pressure on them, and they just somehow take it on themselves, because kids see their parents as successful and worry that they have to be so successful,” she recounted. She pointed out that even when anxiety isn’t present in the home, it reaches girls through their peers, because “anxiety can get to be kind of contagious among teenage girls,” spreading like a virus attached to their whispered horror stories of the friend of a friend who “got a 4.0 and couldn’t get into college.”

Cremer believes that San Franciscans are trying to address the problem. “Some schools have less homework; some schools have a later start time, so I think it’s moving in the right direction for some schools. But some schools are not.”

Among San Francisco’s public schools the most academically demanding is, by most accounts, Lowell High School, an exclusive magnet school located in Merced Park. One 15-year-old Lowell student characterized her school as a “high-performing, high-stress environment” and acknowledged that “stress is a regular topic of conversation at school. As well as just being academically stressful, there’s a sort of competition – to have the most stress, get the least sleep, take the most AP classes – that it’s often difficult not to subscribe to.” She has “many friends that have or have had disorders like depression, anxiety, and eating disorders. I have had a few friends that were actually suicidal, or had an eating disorder that regularly took them to the hospital.”

Lowell “has a Wellness Center that provides counseling, and a lot of people I know get help from there,” she said, but it “currently has a few issues with the way they run things. They’re closed a lot of the time, which I think can create a lot of problems when people have a mental crisis or serious need that can’t wait until they open again the next day. Since mental illness doesn’t operate on a schedule, I believe it’s problematic not to have a resource for students during all school hours.”

“Besides the Wellness Center,” the student continued, “the actual school administration does a very poor job of decreasing student stress levels. Teachers encourage students to put schoolwork before all mental health needs, and the school refuses to change the extraordinarily early start time – 7:35 – despite research that lack of sleep dramatically increases stress and risk of anxiety and depression. Occasionally they’ll hold a ‘stress-free fair’ in an effort to reduce stress, but most teachers don’t let their students out of class, and one day of getting out of a few classes isn’t really going to help anyone.”

In June, the California State Senate approved legislation to prevent middle and high schools from starting classes before 8:30 a.m. If the bill – which is opposed by the California Teachers Association, a 325,000-member body whose spokespersons have condemned as a “one-size-fits-all mandate” that’ll strip “local communities” of their “power of choice” – passes the Assembly and is signed by the Governor it’ll take effect in 2020.

One father of a 16-year-old Lowell student noted that, unlike most of the kids at the school, his daughter “doesn’t care that much about being academically great,” but she still feels the pressure baked into the campus climate, where the classroom’s cutthroat ethos pervades the schoolyard. “It’s more of a social thing. At a school like Lowell, you have a lot of kids who are highly competitive and really into comparing, and that’s really a tough environment for her because her values are different,” he said. “She developed a huge amount of insecurity around her looks, to an extent that she wears huge amounts of makeup and can’t stop doing that.”

“I think technology plays a role here,” the father theorized. “The fact that photos of everything get shared all the time, the whole Facebook thing and Snapchat and people texting pictures: ‘Is this a hot guy or not?’”

Another Lowell parent echoed the sentiment, arguing that social media “encourages a lot of comparison, and it encourages a lot of girls to feel not as good about themselves as they would otherwise. I think it’s a huge problem.”

Dr. Cremer supported the hypothesis that “the social media component” of teen anxiety is “more prevalent with girls: that constant checking, that constant evaluating and being evaluated.”

Dr. Zorbas has similar, perhaps more troubling, observations about the dangers of social media among Bayview teenagers, where “there’s a lot of blackmailing” of girls who “maybe will send a video or a picture of something to a boy they’re dating, and then something goes bad, and now he’s blackmailing them to do different things, or he’ll post on Facebook a picture that was sent to him. All the kids had phones; I don’t care what their income level was,” Zorbas asserted.

Anxiety and mental illness among teenagers aren’t unique to San Francisco. According to Dr. Jess P. Shatkin’s 2015 book Child and Adolescent Mental Health, “anxiety disorders are the most common psychiatric condition in adolescents, affecting 32 percent of 13- to 18-year-olds” nationally. In the U.S., suicide rates have tripled over the past 15 years for girls between the ages of 10 and 14.

“I think there’s more insecurity in general in the world,” Dr. Cremer speculated. The constant media access made possible by technology has connected teenagers to more distant yet still anxiety-inducing issues of national and worldwide significance, from terrorism to climate change. “I’ve had young kids talk about global warming. Is it going to be too hot out? Are we going to be flooded by the ocean? They have worries, and those aren’t crazy worries to have.”

For some San Francisco kids, global problems have a less abstract impact on their lives, according to Dr. Marina Tolou-Shams, a clinical psychologist and professor at the University of California, San Francisco, who leads the Division of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychiatry at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital. “Our population at SF General is a MediCal population, and it is predominantly communities of color, primarily Latino, Spanish-speaking,” she said. “I think what we’re seeing here is a very heightened sense of anxiety, particularly as it relates to immigration issues and the social and political climate of our country right now, and families being torn apart. So, for these young girls who are actually threatened with the loss of a primary caregiver in the home, this is really triggering even more anxiety and difficulty attending school because of fear of separation or because of fear that someone’s not going to be there when you go home.”

Tolou-Shams spoke of “the fear of just being Latino in this day and age” and observed that “it’s something that prior to recently we did not hear Latina girls talking about as much.”

“We know that adolescent girls experience higher rates of depression and anxiety in their teen years than boys, and those gender differences are pretty resolute,” she said. “The other area I work in is juvenile justice. I have one project that’s focused on supporting girls in reducing their drug use; marijuana use is prevalent among teen girls. Girls have unique pathways into the justice system that contribute to their mental health and substance use difficulties. For example, girls who come into contact with the justice system have typically been running away from home for some period of time, so there’s a lot of family issues and often histories of incarceration and mental health within their families that have been unaddressed, and they’re being picked up from being on the street, and substance use is often a contributing factor to that. And trauma: girls who are entering the justice system have a significantly greater likelihood of having a trauma history – often a history of sexual abuse that contributes to trauma and depression and anxiety – which is not necessarily the same for boys.”

Tolou-Shams is trying to “come up with gender-responsive ways to address the concerns in the community. Research suggests that we should be thinking differently for adolescent girls versus boys – not to say that adolescent boys shouldn’t have their own specific engagement approaches into mental health and substance use treatment, but there’s definitely a vision toward more relational, gender-responsive approaches to engaging young girls in mental health treatment, so we decrease the stigma and increase the level of familiarity and comfort, so that they’re more likely to turn to treatment versus engaging in unhealthy behaviors to cope with depression or anxiety, such as substance use or self-harm.”