On the first Tuesday of a picture-perfect August evening, dozens of Dogpatch Neighborhood Association (DNA) members, Southside residents, concerned citizens, and civil servants packed a small community room at the University of California, San Francisco-Mission Bay police headquarters to vet the City’s latest proposal to site a Navigation Center (NavCenter), catering to the homeless, at the eastern end of 25th Street. Meeting attendees greeted the proposal with a mixture of hope, fear, dread and distrust.

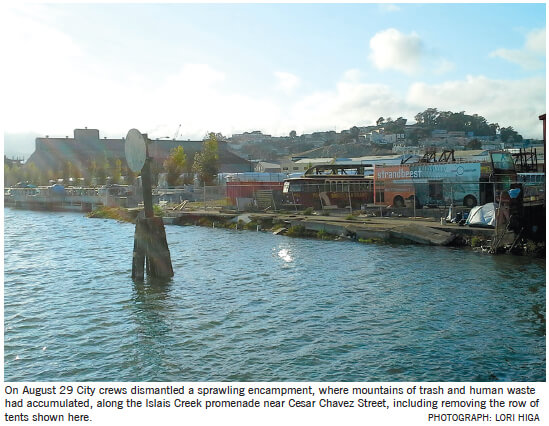

Dogpatch has long attracted what sociologist-author Teresa Gowan labeled “Hobos, Hustlers, and Backsliders…,” many of whom lived in campers and makeshift dwellings on Illinois Street and in, under, and around Interstate-280 overpasses. Recently, though, as the previously blue collar neighborhood has increased in population and household incomes, concentrations of homeless encampments have sparked intensified conflicts. Of particular concern has been a camp with upwards of 50 people living along Islais Creek, on Port of San Francisco property. But that’s just one of a dozen roving tent villages and RV clusters that’re raising residents’ hackles, including intermittent bivouacs at Progress Park, Potrero Avenue, Alameda Street, and a host of other locations throughout Dogpatch, Potrero Hill and Showplace Square.

The two-hour meeting was led by 18-year Dogpatch resident and DNA president Bruce Huie, who brought to bear all his diplomatic skills as he refereed between the City and attendees for and against the NavCenter. An unusually large contingent of public servants participated in the gathering, including staff from the Port, District 10 Supervisor Malia Cohen’s office, and U.S. Department of Homeland Security (USDHS). Also in attendance were representatives from the Potrero Boosters, Green Benefits District (GBD) officers, owners of local businesses Piccino, Yield, and Pearl, and personnel from Pier 70 developer Forest City Enterprises. Conspicuously absent was the San Francisco Police Department (SFPD), which DNA considers key to the proposal’s success.

The City’s Homeless Outreach Team (HOT) had staged an intervention a few days before the meeting to begin clearing out Islais Creek. Jason Albertson, caseworker and point person for “resolving” the tent village, updated attendees on the status of the “Islais Creek Encampment Resolution Plan.” About five individuals had moved to one of the City’s two existing Navigation Centers; another five were waiting for placement. Albertson referred to the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessless’ best practices as guiding municipal efforts to assist homeless exits from the encampment.

Complicating matters at Islais Creek and elsewhere is that many camps are located on property managed by multiple agencies and jurisdictions, including the Port, San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency (SFMTA), California Department of Transportation, and Caltrain. The Port has to coordinate with multiple law enforcement agencies, such as USDHS, California Highway Patrol, SFPD, San Francisco Fire Department, and private patrols

Sam Dodge, San Francisco Housing Opportunity, Partnerships, and Engagement’s (HOPE) director of public policy, shared a 10-minute PowerPoint presentation that, he said, incorporated DNA’s recommendations on a proposed memorandum of understanding (MOU) for the NavCenter. Dogpatch resident Jeff Zacuto erupted angrily in response to a slide indicating the City’s intent to keep the facility open for almost five years, and rebuked Dodge for breaking a promise that the NavCenter would only remain in service for three years. Zacuto said that Dodge could pack up and leave “since the rest of your presentation has absolutely no credibility.”

Huie called for calm, as Dodge changed places with a Department of Public Works (DPW) architect, who spoke about the NavCenter design. Later, in response to an attendee’s spirited objection to the facility’s 24-hour, seven day a week operating hours, a young San Francisco Human Services Agency staffer said, “We’ve actually found from our shelter experiences that it is safer for the neighborhood to keep the center open 24/7 because it reduces long lines.”

Before launching the half-hour question and answer session, Huie warned municipal representatives that it was “now time to get community feedback,” stating that comments would be “candid, pointed and neighborly.” A cross-section of Southside residents and DNA board members voiced a litany of concerns, wanting reassurances that there’ll be a consistent police presence and response time, expressing fears that the NavCenter would bring more crime and homeless to the area; asking for information about the specific resources the City would bring “right now in Dogpatch” to deal with the homeless and the methods HOT uses to encourage homeless to leave or move into services, and wondering what the community could do to help.

“We are doing everything we can to provide options, for better quality of life and less danger for the residents,” Albertson emphasized.

To resolve issues at Warm Water Cove, Port deputy director Tom Carter reported “we are successfully implementing daily drive-throughs by SFPD, Homeland Security and private patrols.”

Albertson explained that SFMTA owns the property west of Islais Creek, San Francisco Public Utilities Commission is responsible for the property east of Indiana Street, and that both agencies are “working with us and DPW to keep the area clean.”

Carter said that Port signage and codes should help with enforcement, noting that “no camping, no sleeping between 10 p.m. and 6 a.m. are allowed on Port property.”

The federal government requires the City to do a point-in-time (PIT) count every two years; the last one in 2014, according to Dodge. Over the past 10 years, San Francisco’s homeless population has increased, from 6,400 to 7,600 individuals, according to the 2014 PIT count. “We’ve seen a lot of condensing of spaces,” Dodge said, “but our own count shows 3,500 people on the street right now.”

Audience members questioned the City’s effectiveness at eradicating encampments. “Absent solutions…and with sanitation and health issues, the situation is very much a game of whack-a-mole,” Dodge admitted.

Albertson intervened, calmly reciting HOT’s methods. “We approach people with a variety of social services, give good compelling offers that are real, that have continuity with 24/7 outreach, even if they’re not ready,” he explained. “When people move, we lose connection. Clients shouldn’t have to hold for continuity of care. We really need a system in place so that when we’re in the field, we can pull up information on the client…so that we don’t lose the case file. Anyone should be able to access data. In a City with tech companies like Google, information should be in the cloud.”

An attendee who said he was the president of a Minnesota Street homeowners association carefully pulled out objects from a heavy-duty shopping bag and placed several bio-hazardous containers and a clear plastic soda pop bottle missing its cap crammed full of syringes on the table. “Can any of you take these? We don’t want them. Our HOA shouldn’t have to be doing this. We have lots of children in our neighborhood.”

The display prompted Rhonda to ask, “there seems to be a huge increase in drug use among homeless people, are you seeing that?”

“No, we haven’t seen that,” Dodge replied. “There has been a huge increase in IV drug use. But there’s always been open drug markets, meth use; drug use is not a new problem but IV use is an increasing problem.”

GBD executive director and former District 2 Supervisor Julienne “Julie” Christensen prefaced her question by referring to significant cuts in state and federally-funded subsidized housing, which the City responded to by increasing its shelter expenditures, and the San Francisco Board of Supervisor’s rejection of an $80 million expenditure for a new jail, recommending, instead, that the funds be used to provide mental health services. “So, what’s the plan on housing, how are we doing with housing and mental health services?”

“We’re not just working on housing for Islais Creek, we’re working with the Salvation Army, who offers beds and substance abuse treatment, and HealthRight 360, which just ate Walden House, Lyon-Martin and Women’s Recovery Services. So we’re not just looking at housing because there’s not enough shelter,” confirmed Albertson. “Shelters are not appropriate for everyone. We do link them to primacy care services, with a number of packages that apply, both large and small,” he said.

The turnover in supportive housing is 10 percent, according to Dodge, who implied that a continuous housing pipeline was available for homeless clients. “There’s VA funds, federal funds and City funds…we’re having great success with rapid re-housing and rent subsidies, where we have a 90 percent success rate.” Working with organizations like Swords to Ploughshares, Dodge noted a 50 percent decrease in homelessness among vets nationally. “We’re partnering on housing supports with HUD; in San Francisco, we’re able to leverage Obamacare, use Medi-Cal to pay for support services to help veterans.”

“We could use a better Congress regarding programs for state mental health services,” Albertson joked.

“LA County has over 50,000 homeless,” said Dodge. “Santa Clara is closer to San Francisco, with 6,500 homeless. In California 70 percent of homeless are unsheltered, but the problem seems to be particular to California. There is some hope looking forward. We have to segregate our resources and target our efforts, it’s a dynamic situation. Some need a lighter touch while some, the chronically homeless, have spent 40 years on the street.”

“It sounds like a regional issue,” said GBD board member Janet Carpinelli. “San Francisco needs regional help. How do you track people? How do deal with follow-up of people in the area? We’ve stepped up to the plate with the NavCenter. Skateboarders are the last holdout at Warm Water Cove. No one else goes there anymore because people don’t feel safe. We’re talking about a place that was originally a $6 million park for all of San Francisco not only for homeless people.”

“Our goal is to build therapeutic relationships,” Albertson replied. “The plan is to keep track of homeless clients and work with partner agencies wherever we can.”

Dodge is working with social service agencies, “at the Hamilton Family Center, Swords to Ploughshares…agencies in the East Bay who end up housing our people. My East Bay colleagues are becoming more sophisticated. They are putting bonds on the ballot for both affordable housing and supportive housing. I am more and more hopeful.”

“What is the game plan, what numbers do you want to see in three years?” asked an attendee.

“Let me address that,” said Jeff Kositsky, the newly appointed head of the just-created Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing. “DHSS represents the first time the City has a plan to centralize and coordinate all agencies serving the homeless under one roof. We’re creating one center of gravity, so people know who’s responsible, who’s working with the police, the fire chief, the Port. It’s a business, data-oriented approach. For example, the City has 12 different data sets on homeless and now we’re creating one database. We’ll have a website with a dashboard that anyone can access and we’ll be doing quarterly reports. The police department will report quarterly to the neighborhood. We also want to establish an advisory body with NavCenter residents, contracted service providers, DHSS and the neighbors. One thing we’re working on with the Corporation for Supportive Housing is a gap analysis to find out where we’re short on things like beds. We must first breakdown the homeless into categories; they’re not all the same. One goal we have is to end chronic homelessness among veterans by mid-2017. There are 1,700 chronically homeless individuals. Give us a couple of months to improve, coordinate and collaborate. Our goal is to cut the number of homeless by 50 percent within the next few years. We are striving for transparency.”

The City spends about $50 million a year on outreach, shelters, drop-in centers and transitional housing Dodge explained. “One hundred forty million dollars a year goes to supportive housing, addiction prevention and health care.” The City invests a total of $241 million a year on homeless services, he indicated, “but that figure does not include DPW, costs for cleanup and emergency room costs. By comparison, Santa Clara spends $1 billion a year and only a small percentage is spent on health care.” Dodge estimated that the City has about 9,000 formerly homeless individuals in permanent supportive housing.

Albertson advised Dogpatch residents to call 311 if they see a tent going up, claiming that there’ll be a response within 72 hours. “We also recommend that pedestrians avoid walking adjacent to the SFMTA property and only use the north side of 25th Street for safety,” he added.

Meeting attendees criticized the City for a lack of transparency, questioned whether the Port was engaged in properly maintaining Islais Creek, and wondering why SFPD didn’t attend the meeting. Others reiterated their frustration with crime, as well as SFPD’s lack of response and claims that their “hands are tied.” A former Pacific Heights resident, who now makes Dogpatch her home, politely called attention to what some see as the City’s hypocrisy. “You talk about sharing resources, but I don’t see that happening here. I lived in Pacific Heights for decades and the police did a good job of moving people along. I don’t see the police doing that here.”

Local real estate consultant Joe Boss wondered whether the police ever check chronic crime areas, “like the Shell gas station, the Loop. It seems like crimes are always being committed at these spots, and when you go down there and talk to management about calling the police, they say we do call, but the police don’t do anything.”

“Did you get that?” Huie asked Dodge and his team at the end of the meeting.

A DNA board member made a motion to vote on the proposed MOU at the September meeting, contingent on DHSS providing a final draft to review seven days in advance, which a majority of DNA members approved.