Halfway into a three-year lease, the Dogpatch Neighborhood Association (DNA) is generally supportive of extending the Central Waterfront Homeless Navigation Center’s stay and expanding its number of beds from 63 to 68.

A presentation last fall by the City’s Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing (HSH) to DNA drew a positive response. DNA president Bruce Huie confirmed that “because of good results and no issues over the past 18 months” the Association is considering endorsing another three-year term.

There were mixed feelings in Dogpatch when the navigation center first opened in May, 2017 on Port of San Francisco-owned land at the end of 25th Street. While there were a number of proponents, including former District 10 Supervisor Malia Cohen, opposition led the Port to shorten what was originally supposed to be a four-year lease.

Developed in San Francisco, with the first one opened in the Mission District in 2015, the navigation center concept has since spread to Santa Rosa, Seattle, and Austin, Texas. The facilities allow for longer stays than overnight drop-in shelters and provide support staff to assist people secure permanent housing or employment. San Francisco now offers facilities located at Division Street, Civic Center and, for those with serious mental illness or addiction issues, Hummingbird Place at San Francisco General Hospital. Another center will open on Bryant Street this month. The Mission center recently closed to make way for an affordable housing complex.

The centers were established to serve the chronically homeless, people who have traditionally shunned shelters and assistance and thus been harder to reach. “They are designed to meet people where they are at,” explained HSH spokesperson Randolph Quezada, noting that the abundance of rules at shelters often keeps people away.

John Ouertani, Central Waterfront facility site manager, cited what he calls the three Ps: property, partners and pets, all of which are accepted at navigation facilities. “Shelters have two-and-a-half pages of rules. They need to because they are larger, with 200 guests,” he said. Shelters separate people by gender; navigation centers don’t. “That’s a barrier for some people,” he explained. “Here you can have two beds next to each other.”

At the Central Waterfront, Ouertani said staff mainly pays attention to behavior. The only major rule is no violence or weapons. “Our goal is to keep them here,” he said.

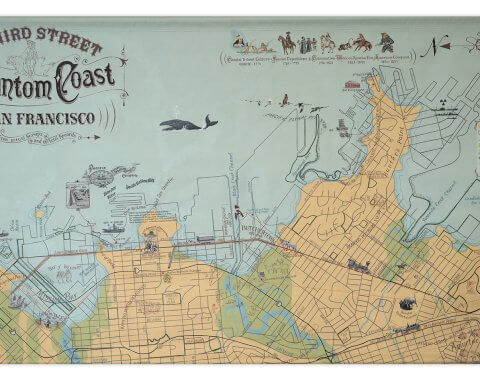

Located away from residences, the 14,000-square foot complex is on a dead-end street sandwiched between an industrial crane and rigging firm and a San Francisco Municipal Railway light rail car maintenance facility. It consists of four dormitories, male and female bathrooms and showers, a nurse’s clinic, staff offices and a community center for events and food service. All of the modular-style buildings open to a large outside seating area with picnic tables.

While the center is funded by the City, it’s staffed by Episcopal Community Services (ECS), which had operated the Mission Navigation Center. ECS has a dozen people working at Central Waterfront, including four case managers.

Initially the City underestimated the length of time it’d take those case workers to stabilize clients, setting a one-month limit. ECS spokesperson Jenn Soult explained that for many identification and other personal documents needed to obtain housing or employment have gotten lost over their time living on the streets. Other obstacles, such as criminal records or handicaps, need to be overcome. “People come in very raw,” she said.

Clients are now discharged when they move on to housing, or until they reject or stop working toward their options. Stays at Central Waterfront often run between two to five months, sometimes as long as a year.“We have a few different types of beds available,” explained Quezada. “We have pathway to housing beds, where guests prioritized for supportive housing may stay in until they’re placed. We also have time limited beds where guests may stay for 30 to 60 days.”

Another option, known as the homeward bound program, is to accept bus rides out of the City to reconnect with friends or family elsewhere.

Quezada said the Central Waterfront facility has served 282 individuals thus far and has generally been at full capacity. Seventy individuals have exited to housing, six to other temporary placements. Six reached the end of their time-limited stay; 132 left on their own, designated as “unseen for 72 hours.” Forty were discharged due to rule violations, although a crosscheck of police reports indicated none that’ve been filed at the location.

“You need a thick skin,” admitted Ourtani, who said staff is trained in de-escalation tactics. Ourtani worked at the Mission location when it opened, and for six years prior at The Sanctuary and Next Door, two shelters also operated by ECS. He likens his role as to working a customer service job. “Just because people aren’t paying doesn’t mean you don’t have to provide them good service,” he said.

ECS relies on a variety of food donors, including Meals on Wheels, and has volunteers who assist or hold events. Adobe hosts game nights once a month. “Name any large tech company in San Francisco and they volunteer with us,” said Soult.

Some of those companies, through corporate responsibility programs, offer matching grants for employees who donate time or money. Adobe, for instance, provides a $250 grant for every 10 hours of volunteer service an employee engages in.

Navigation centers were established to work in conjunction with tent camp removal. Rather than allowing drop-ins or referrals, only the City’s Encampment Resolution Team or Homeless Outreach Team can place people. There are no wait lists, said Quezada. Placement is done in “real time,” meaning that teams know where openings are available at a given moment. Still, despite navigation centers’ increased flexibility many refuse help. “There is a community in those encampments,” explained Soult. “Separating them can be an issue if there are only two beds here and two beds somewhere else.”