Construction of the Potrero Terrace and Annex housing complex was catalyzed in 1937, when the U.S. Congress passed the Housing Act as part of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal, a package of legislation and initiatives enacted to help the country recover from the Great Depression. Other New Deal elements included banking safeguards, such as the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and creation of the Social Security Administration. The Housing Act was designed to provide safe and affordable residences for low-income families.

In 1938, San Francisco created the Housing Authority (SFHA) to manage Housing Act subsidies. SFHA is the oldest such entity in California. Two years later, the Authority opened Holly Courts, the first public housing development west of the Mississippi River, in Bernal Heights. Other complexes, including the original 469-unit Potrero Terrace, were completed by 1943 and were mostly occupied by war industry workers, with Annex added in 1955.

Roughly 60 years later, in 2005, many affordable housing developments had been neglected into poor condition. Renovating them would require an estimated $267 million investment, or more. After consulting with residents, businesspeople, and civic leaders, then-Mayor Gavin Newsom, along with former District 10 Supervisor Sophie Maxwell, created HOPE-SF, a collaboration between the Housing Authority and Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development (MOHCD). The plan was to rebuild four of the most severely deteriorated public housing sites: Alice Griffith, Hunter’s View, Sunnydale-Velasco, and Potrero Terrace-Annex, tripling the total number of housing units across these developments from 1,900 to more than 5,300.

A decade went by. Proposition A, which voters approved in 2016, provided $310 million in bond monies to fund construction at Sunnydale and Potrero. BRIDGE Housing Corporation (BHC) secured the contract to “Rebuild Potrero.” In 2019, an initial 72 units were opened for occupation at 1101 Connecticut Street.

Next up, according to Eric Brown, BHC Senior Vice President of Communications and Policy, is Potrero Block B, located at 1801 25th Street. Planned for a mid-2025 opening, Block B will house residents earning between 30 and 60 percent of the area median income, currently $105,000 for a single person, $150,000 for a family of four. Block B will have 117 units for former public housing inhabitants, 38 apartments for low-income occupants, and two manager units.

Terrace-Annex residents are first in line for an apartment. Three-quarters of the Block B units will serve as subsidized replacements for current Terrace-Annex residents. The remaining residences are affordable/income-restricted, with priority given to former and existing Annex-Terrace inhabitants.

It wasn’t supposed to take 20 years to build less than 200 residences. Part of the delay was caused by the need to re-classify public housing as mixed-income neighborhoods, with some units sold or rented at market rates, others reserved for low-income households. The mixed-income model originated in the 1990s, with the federal Hope VI program, based on the successful transformation of a failing public housing development, Columbia Point, into a mixed-income apartment complex in Boston, Massachusetts.

Pursuing this model has been challenging, particularly associated with relocating existing public housing residents. Anxiety about dislocation and gentrification is especially acute in San Francisco, where 1960s “redevelopment” of the Fillmore dislodged a sizeable chunk of the City’s African American community. In the late-1990s, a similar effort to revitalize Bayview-Hunters Point through new construction resulted in a 342 percent rise in housing prices. The real estate runup, combined with toxic mortgages, forced out many of the neighborhood’s Black residents.

The Potrero plan is supposed to overcome these challenges through land sales to private developers, who will build 817 market-rate rentals and condominiums along with 200 low-income or below-market units. In addition, Terrace-Annex’s 600 public housing units would be replaced one-for-one.

“This increase in density,” said Anne Stanley, MOHCD spokesperson, “allows for the replacement of all the public housing, plus new affordable, plus market rate housing, without displacement.”

Terrace-Annex residents must be temporarily relocated so their units can be torn down and replaced. Those inhabitants then move back into the new residences. According to Brown, Block B residents were moved to 1101 Connecticut after it opened, and the associated vacated buildings demolished.

Every replacement 1101 Connecticut unit was leased to a legacy Annex-Terrace resident, with inhabitants given first preference for any future replacement unit that becomes available in the building, followed by Sunnydale residents who have yet to relocate into a new unit.

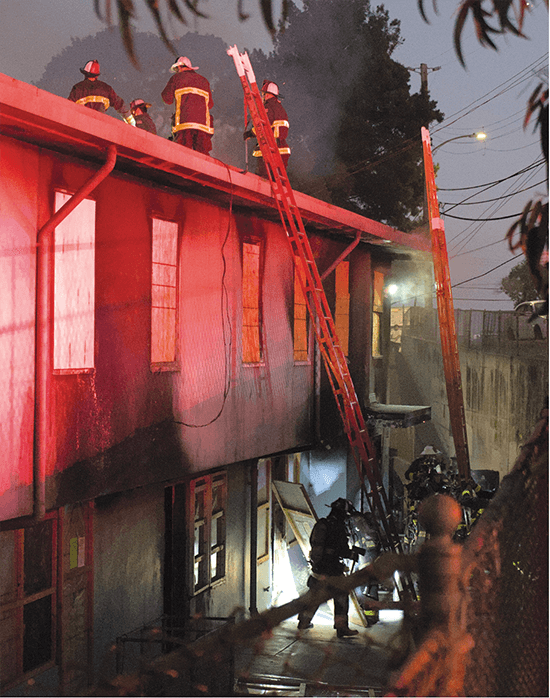

Meanwhile, Terrace-Annex has been poorly served by the Eugene Burger Management Corporation (EBMC), which took charge of property oversight in 2022. The private-sector firm failed to perform necessary maintenance and did little to prevent squatters from occupying vacant units scheduled for demolition. In 2023, a fire in a unit that was supposed to be empty killed one person and forced others living nearby to move. Fire Department investigators suspect trespassers were responsible.

Earlier this year, reports emerged that Lance Whittenberg, an EBMC employee, had allegedly been renting vacant units, collecting monthly payments in cash, which he’s accused of pocketing. Whittenberg was fired shortly before accusations against him became public. However, the San Francisco City Attorney office said it could find no evidence that property management staff was collecting rent off-book from Terrace-Annex squatters. “While we found no corroborating evidence that any off-lease residents paid Whittenberg, three off-lease residents reported being extorted by unknown men under threat of violence,” the City Attorney stated.

Last fall, the City took legal steps to evict the squatters, many of whom believed they were legitimately renting the units because they were paying Whittenberg. In response, the Eviction Defense Collaborative, a nonprofit that helps low-income tenants respond to eviction lawsuits, asked the Housing Authority to halt the expulsions.

EDC Community Outreach Senior Litigation Attorney Jessica Santillo said SFHA refused to stop the evictions, vacate judgments against residents who didn’t respond to notices on time, place eligible Terrace-Annex residents on a waitlist for portable housing vouchers, or allow residents to remain in their homes until alternative subsidized housing could be found.

“Most disturbingly,” she added, “they refused to even meet with residents to draft a plan to relocate rather than turn them out to the street.”

Stanley countered that MOHCD, alongside SFHA, has provided information to the impacted occupants on how to access shelter and referrals to the office’s Tenant Right to Counsel partners.

In a wrongful death lawsuit filed last month, Ralph Gescat asserted that Annex-Terrace was egregiously mismanaged, becoming a death trap for his 40-year-old son Richard Gescat, who perished in a 2023 blaze in an abandoned building at the site. Mission Local reported that Gescat was likely a squatter living on the property.

Under pressure from the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, demolition approval of Annex units was granted last fall by the Housing Authority and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

“Because Potrero HOPE SF is a long-term multi-phase project that includes the construction of new streets, parks, and other community improvements in conjunction with new buildings,” Stanley explained, “every phase requires careful and intentional engagement with residents, as well as the development of detailed relocation plans prior to starting the next phase of demolition.”

Although there are numerous vacant Terrace-Annex units, few buildings are entirely empty. Demolition can’t be executed until those residents are relocated to off-site replacement residences or in Potrero Block B when it’s completed.

EBMC’s contract expires in January. The Housing Authority intends to issue a request-for-proposal for a replacement. In September another fire broke out in the same building as the one in 2023, suggesting squatters continue to be a problem. The entire Potrero project is supposed to be completed in 2034, almost 30 years after the rebuild was first contemplated.