Access to housing, and the associated social ills of unaffordability – sprawl, crowding, commuting, homelessness – is a perennial political hot topic in San Francisco. Most everybody wants to increase the supply of inexpensive residences, though there’s often pushback on specific proposed projects, principally based on lifestyle concerns, such as increased traffic, blocked views, and a degradation of community cohesion and architectural integrity.

Lurking behind the debate is a host of largely unexamined questions, including the overall purpose we want our built environment to serve, and its preferred characteristics.

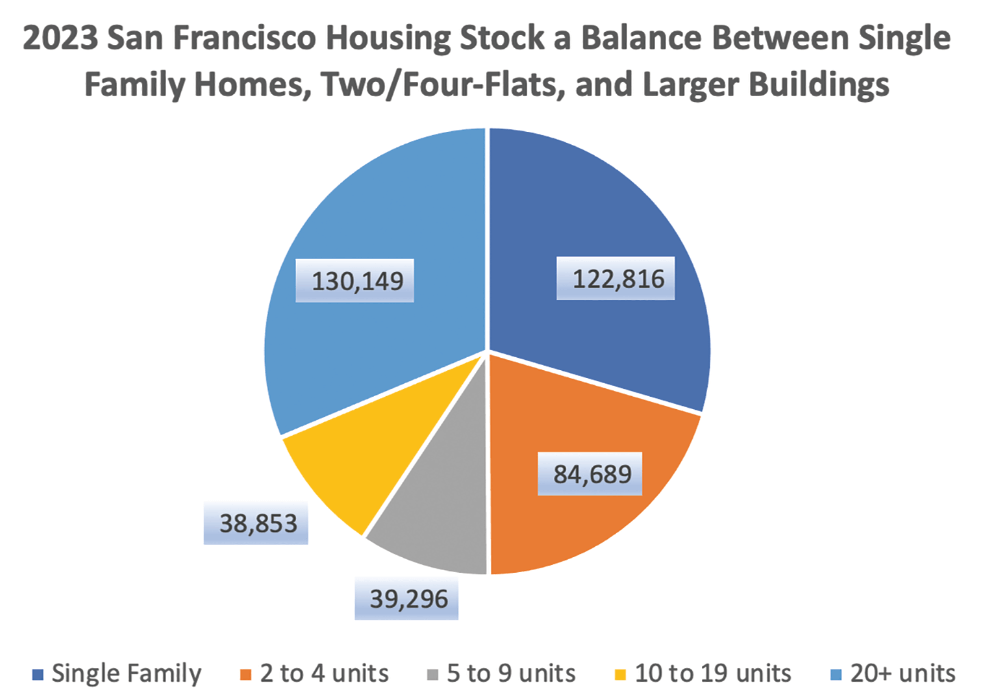

San Francisco isn’t defined so much by its tall buildings – which until recently were largely limited to Downtown – as its low-slung neighborhoods, which feature a mix of modest multi-flats and single-family houses. While most of the population lives in places with more than 10 units, overall residential buildings are almost equally divided between structures with fewer than nine apartments, dominated by stand-alone homes, and more densely packed big-buildings.

This housing mix creates a particular social and political flavor. In part because of the dominance of multi-family buildings, large and small, almost two-thirds of households rent. People don’t tend to stay long. Forty-five percent San Franciscans have lived here for less than six years. As a result of their short tenure, they mostly ignore politics and avoid community engagement, though happily contribute to a vibrant restaurant and bar scene. Just 20 percent of the population has made the City their home for more than 25 years. These characteristics contribute to the consistent split between electing generally moderate mayors and more liberal supervisors, near-constant public-school turmoil, and continuous chatter about where to eat, drink, party, and find someone to date.

The built balance is steadily tipping towards larger multi-unit medium-rises, with associated implications to the concentration of renters and short-timers. Over the last eight years residential construction has been dominated by structures with five or more units. Barely any single-family houses have been erected. San Francisco has long been a city of flats, many of them renovated Victorians with former dining rooms and parlors repurposed as bedrooms. The San Francisco of the future will increasingly be defined by box-like apartments, featuring consolidated amenities, such as gyms and common spaces, reducing the need to travel outside one’s tower.

Given these development trends, San Francisco will more and more be occupied by tourists, some staying for a long weekend, others for a several year hiatus. The associated social and political consequences could include greater pressure to rent control newer apartments, a continued diminishing population of children, and an ever-vibrant entertainment and foodie scene. It could also cultivate a constant pulse of creativity, a cycle for which San Francisco has long been famous, as the in-and-out tide of new arrivals brings new ideas, new identities, and fresh energy.

Without an unexpected dash of design innovation, however, architecture will become ever duller. It’s unlikely that any future San Franciscan will get excited about touring buildings constructed over the last 50 years, or many visitors will line up for Insta-ops in the same numbers as Alamo Square attracts.

Higher density residences tend to feature fewer bedrooms, reinforcing the notion that what’s being built is most suitable for younger, single, workers, with high prices squeezing those with little choice, or tight extended family preferences, into tinier spaces, part of a nationwide phenomenon. Two-thirds of the units constructed over the past seven years were two bedrooms or smaller. That’s in part because it costs at least $600,000 to construct a unit of that size, barely affordable to rent or buy for a dual income couple earning San Francisco’s average income.

Taken together, small home sizes and high construction costs suggest that increasing housing supplies will not substantially reduce rents or prices, at least in ways that match income. That is, a supply-side strategy alone will not improve housing accessibility. That’s only likely to occur with massive investments in subsidized residences, higher wages, and/or an efficient transportation system that delivers people to lower-cost areas.

The type and cost of new residences being constructed reinforces San Francisco as a steppingstone to move out as income rises and/or children appear. While there’s steady, if slow, development of modest-sized apartments, the next size up remains largely static. The COVID pandemic – with associated school closures and remote work – was a significant factor in an 18 percent decline in San Francisco’s under 30 population between 2020 and 2023, with the largest decreases among kids not yet in kindergarten, a 15 percent slump, and those aged 25 to 34, a 20 percent drop. The only age group that saw significant increases were 70- to 80-year-olds, a testament to San Francisco’s superlative health care options, the type of apartments being built, and the amount of money needed to occupy them.

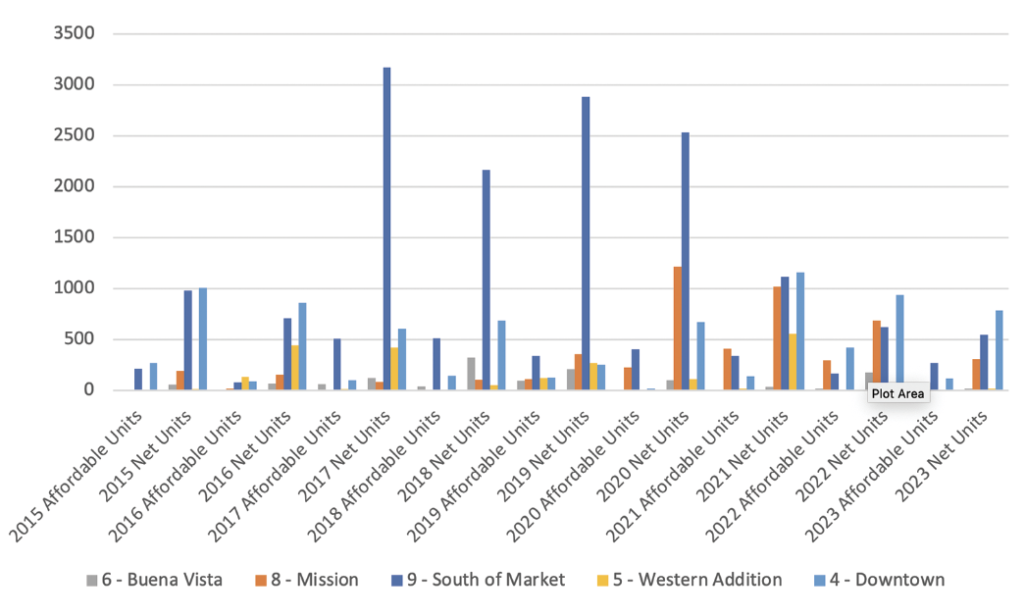

San Francisco’s population is tilting towards the southeast neighborhoods, with most new residential construction taking place “South-of-Market,” a designation that in this case includes Mission Bay, Dogpatch, and Potrero Hill. With the potential opening of Mission Bay Elementary School in 2026, those neighborhoods offer an interesting experiment in residential retention. Will a brand-new campus, alongside beloved Starr King and Webster elementary schools – assuming they scape the public school chopping block – as well as renovated Crane Cove, Esprit, and, ultimately, Jackson Park, successfully argue for families to keep their kids in the City? We’ll know by the end of the decade.