Tommy Egan was a well-known, much loved and respected, although generally drunk, former professional boxer who lived on 20th Street between Third and Illinois streets during the second half of the 20th Century. In Tommy’s lifetime the area was referred to mostly as “lower” Potrero Hill. Today it’s within the boundaries of “Dogpatch,” which has expanded from roughly a city block to today’s much larger booming community.

Thomas (Tommy) Leo Egan was born October 30, 1924, to George Egan and Mayme (Ayoob) Egan. He grew up in a multi-unit building, one of the first built in Dogpatch, on the corner of 18th and Tennessee streets, which was owned by his mother’s side of the family. He lived there with his parents and maternal grandparents as well as other family members. For many years a grocery store was located on the bottom floor.

Years later, Tommy rented a room in a former boarding house for industrial workers located on the west side of Third Street, between 20th and 22nd streets. The building offered quarters for rent and a shared bathroom. He lived there until his death in 1996.

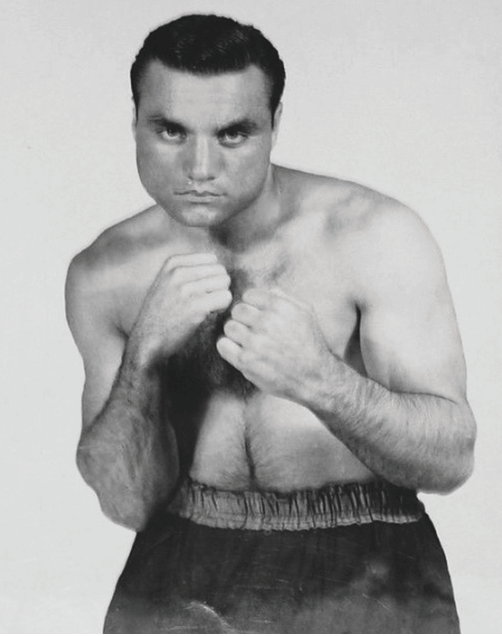

In his prime Tommy was a welterweight boxer and marine. In his later years a casual passerby might judge him to be a scruffy ol’ drunk. Yet no matter how inebriated he might get he always maintained his self-respect, and his respect for others. He may have enjoyed getting sozzled, but he wasn’t a fool. His neighborhood reputation was as a great boxer, standup honest straightforward guy. Whether he was a good husband to any of his many ex-wives or a great father to his children is a different matter.

Of the four bars on the block, Tommy’s favorite was Tom’s Drydock, later known as Mucky Murphy’s, occupied by Third Rail Bar today. Tommy would occasionally visit other saloons, staying a short while before heading back to Tom’s Drydock.

Tommy would arrive at Tom’s Drydock early in the morning when they opened. He’d be drunk and ready to depart by roughly noon. Bar patrons and neighbors would take turns walking him home if he looked like he was wobbling too much. Third Street was busy and sometimes dangerous to cross; community members wanted to make sure he got home safely without getting hit by a car or falling.

Once when I walked Tommy home, I greeted an older gentleman, known as “Smitty,” walking towards us on Third.

“Don’t say “hi” to him! He’s a fucking child molester!” Tommy yelled, continuing with other expletives as we walked past.

Sometimes neighbors escorted Tommy halfway home, and he’d take it from there. Occasionally he needed extra help to make it to the entrance of his building or all the way up the stairs to his room.

Once I accompanied Tommy to his quarters. After struggling with his keys and finally getting the door to open, he turned on the light to reveal a layer of blackness covering the chamber’s floor. The shadow scattered in unison from the room’s center outwards towards the perimeter of the walls, disappearing. For a moment I thought a supernatural phenomenon had unfolded before us, then realized that what we saw were cockroaches. Thousands of roaches. I watched for Tommy’s reaction; he didn’t have one. It was something he’d seen many times before.

Concerned that he might fall, I waited until Tommy was safely in bed. He sat at the foot of his mattress, fell straight back with his feet still on the floor and immediately went to sleep. As I left, I imagined Tommy laying very still in the dark in his drunken state, with roaches covering his body.

Later I asked my father if there was anything we could do to help Tommy. He responded that there wasn’t; it took Tommy years to get to his condition and it wasn’t easily fixed. He had money, a roof over his head, and he wasn’t hungry. He was happy living life as he wanted to live it.

Tommy was a professional boxer between 1943 and 1948, Over 51 career fights he won 40, 18 of which were knockouts, lost six, though he was never knocked out, with five draws. Tommy had a glass eye that he once tried keeping a secret so he wouldn’t be barred from pugilism; in many of the contests Tommy won, he did so with only one eye.

Judy’s, my mother, favorite memory of Tommy is when he’d take his glass eye out and roll it across the bar. I tried to get Tommy to do this for me, but he declined and wouldn’t budge no matter how much I implored him. I was maybe 16 at the time. I think he didn’t want a young girl to see him that way.

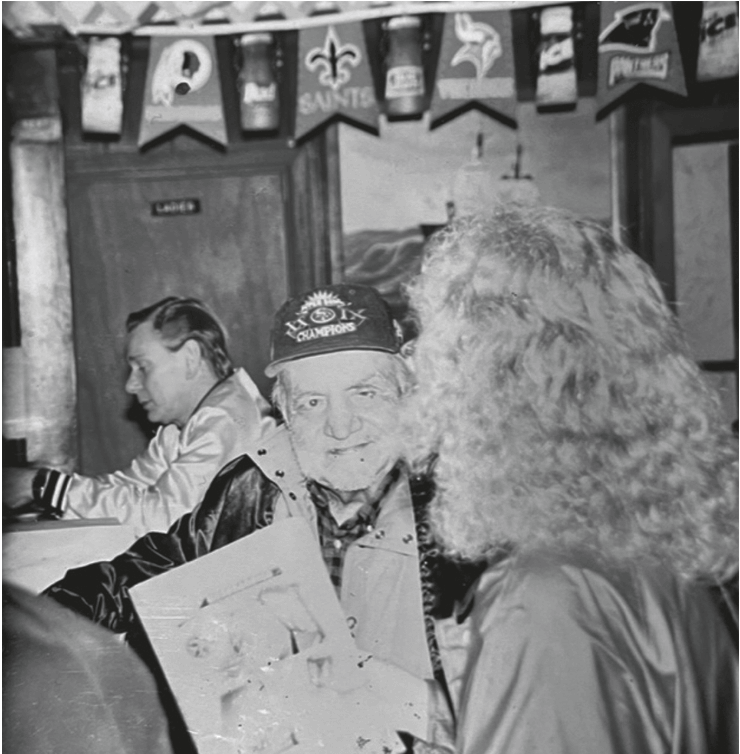

When I was 14 years old, Tommy asked me to go to a boxing award ceremony with him. I was honored but too embarrassed to accompany a scruffy old guy driving a 1950s station wagon stuffed with his belongings. The day he received the prize was the only time I saw him in a suit. Today, I’d dress to the nines and be happy to accompany Tommy to collect any tribute.

Sometime in the 1990’s Tommy was in Tom’s Drydock or its successor. A guy who wasn’t a regular was being rude to other customers, loud, bothering all the patrons. Tommy asked him to shut up several times. The guy kept going on and on and wouldn’t stop. Finally, Tommy had enough. He clocked the guy, knocking him right out.

Tommy died September 27, 1996.