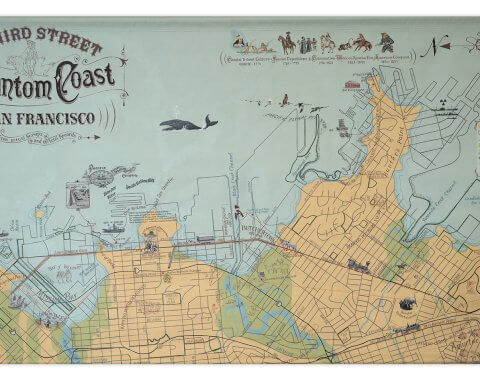

Fourteen years after the University of California, San Francisco built its high-technology research campus on an abandoned Southern Pacific railyard in Mission Bay, much of the surrounding area still feels pretty sterile, lacking a sense of organic human habitation that comes with a diversified, multiuse, street life of restaurants and shops. That’s one reason why the weekly Mission Bay Farmers’ Market at UCSF, which has gradually grown in size, scope, and popularity since it opened in 2009, registers as an important injection of life and color when it sets up on Wednesdays between Third and Fourth streets on the Gene Friend Way pedestrian plaza.

San Francisco hosts 24 regular farmers’ markets, none of them in Dogpatch or Potrero Hill. For Southside neighborhoods Mission Bay’s year-round market is the only game in town. It opens at 10 a.m. closes at 2 p.m., rain or shine, and offers all of the farmers’ market staples: fresh produce, primarily, along with flowers, fish, bread, and a selection of hot prepared foods dished out from tents from which snake long lines of University of California, San Francisco employees at lunch hour. One of the things I especially like is that it has several stands that sell only one thing each, like eggs, strawberries, or asparagus. Is there any better way for an artisanal grower to establish complete dominion over a single ingredient than to sell nothing but that item?

My next major destination, after I left the farmers’ market, was in the Hill. On the way, however, I stopped at the Friends of the San Francisco Public Library Book Donation Center, 1630 17th Street, across from Jackson Playground. From 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. on weekdays, and 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. on Saturdays, this facility accepts donations of books, compact discs, LPs, and other materials that stock not-for-profit bookstores at the Fort Mason Center and the SFPL’s main branch, the revenues from which support the public library. The Friends’ website doesn’t note that the 17th Street Book Donation Center contains a tiny street-facing bookstore of its own; a small garage door opens onto a closet-like alcove of shelves. The unalphabetized collection of fiction and nonfiction struck me as entirely random. There was even a set of instructional martial arts video home system tapes mixed in among the used books. But the chaos is manageable and even pleasant, given how quickly and easily one can browse the nook’s assortment in its entirety.

I love secondhand bookstores because the goods are cheap enough to allow browsers to take a risk on an unknown title. Here, paperbacks cost two dollars; hardcovers three. Choices are purchased inside, at the donation floor around the corner. I bought a book called Le Corbusier in Perspective, an anthology of architectural essays that extend way beyond my limited grasp of the subject matter. There was something so civilized, I thought, about casually picking up an incomprehensible volume of architectural criticism at a miniature parkside bookstand, like a Parisian strolling by the literary vendor carts along the Seine.

From there, I proceeded to the nearby Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts, 360 Kansas Street, operated by the California College of the Arts. Entrance to the Wattis – an impressive modern space designed by Mark Jensen, the architect responsible for the rooftop garden at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art – is free, as is admission to the lectures, performances, and workshops frequently held there. Hours are Tuesday to Saturday, noon to 7 p.m.

The main exhibition, currently, is Henrik Olesen’s The Walk, a challenging installation of new and existing work by a Berlin-based Danish artist whose modus operandi involves upsetting the tidy and precise arrangements of today’s austerely hygienic galleries. His Wattis show leads visitors past pieces that look like art – a jagged black-and-white photomontage, composed largely of infamous subjects of sexual scandal, alongside personal grooming products, like toothbrushes and razors; canvases decorated by rows of sloppily glued metal screws – and alongside items that resemble art world debris, objects that were supposed to be cleaned up and stored backstage before opening, or were never meant to leave the studio, like boxes of unfolded promotional T-shirts, an unplugged clothes iron, and a half-built wooden shed containing what could, from a distance, be a child’s incomplete science fair project. The experience is mildly upsetting, funny, and invigorating all at once.

CCA graduate students have transformed the Wattis’s secondary gallery into a communal gathering space for a project called Black Light that, in a series of events this spring, has spotlighted authors, historians, activists, and artists who have examined “the relationship between cultural institutions and black artists.” The final lecture in the series, which also contains a darkly expressionistic large-scale painting by Rodney McMillan, features the Afrofuturist Rasheeda Phillips on May 6 at 6 p.m.

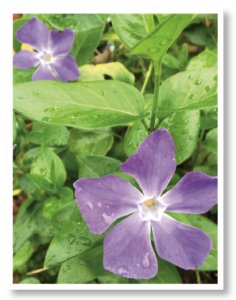

Four blocks from the Wattis is the Benches Garden, 18th Street and San Bruno Avenue. In early 2010, the Benches Garden transformed the blank area beside the pedestrian overpass at 18th into a botanical oasis, becoming one of several small, community-tended, green spaces that perform the vital service of softening the Hill’s eastern and western borders, bounded by noisy superhighways on two sides. Although I’ve always admired the landscaping on both ends of the overpass, I’d never bothered until the other day to enter the flowery fenced enclosure on the Potrero side, just above the benches themselves. It’s a lovely, well-tended, plot; it even contains a Little Free Library where passersby can take a book – in case you didn’t find anything of interest on 17th Street – or leave one behind. The first drawer of the metal cabinet that constitutes the “library” holds books; the second contains homemade music cassettes, the third has magazines. Garden volunteers meet once a month, every first Sunday at 9 a.m.; all are welcome.

Four blocks from the Wattis is the Benches Garden, 18th Street and San Bruno Avenue. In early 2010, the Benches Garden transformed the blank area beside the pedestrian overpass at 18th into a botanical oasis, becoming one of several small, community-tended, green spaces that perform the vital service of softening the Hill’s eastern and western borders, bounded by noisy superhighways on two sides. Although I’ve always admired the landscaping on both ends of the overpass, I’d never bothered until the other day to enter the flowery fenced enclosure on the Potrero side, just above the benches themselves. It’s a lovely, well-tended, plot; it even contains a Little Free Library where passersby can take a book – in case you didn’t find anything of interest on 17th Street – or leave one behind. The first drawer of the metal cabinet that constitutes the “library” holds books; the second contains homemade music cassettes, the third has magazines. Garden volunteers meet once a month, every first Sunday at 9 a.m.; all are welcome.

On the opposite end of the neighborhood, in Dogpatch, a new restaurant, Glena’s Tacos and Margaritas, opened at 632 20th Street, former site of local favorite, The New Spot, which closed last year when chef and co-owner Gilberth Cab was denied an opportunity to renew his lease. Justly embittered The New Spot devotees may have a hard time finding a place in their hearts for Glena’s, but I gave the newcomer a shot. The interior has been redesigned, with a simultaneously sleek and weathered aesthetic, and a hint of tropical flavor. The spare menu offers a short selection of simple, tasty tacos – al pastor, carne asada, pescado, and tofu – at five dollars each. Tacolicious, rather than Taqueria Vallarta, prices. Glena’s is a poco more traditional than the former, obviously less than the latter.

In addition to tacos, my wife and I ordered the fried chicken torta, the vegetales en escabeche, and an agua de Jamaica. We found all of them pleasing and flavorful. However, I was disoriented by the question of how to tip in a fast-casual restaurant environment, in which customers order at the counter, fill up their own water glasses, and retrieve their own silverware from a tabletop bucket, but receive their food from servers at the table, without having to get up for it. At Glena’s, unless you sit at the bar, you pay for your food up front and then immediately select your tip on the computer screen: the percentages suggested by the Square interface were 18, 20, and 25, which, to me, came across as somewhat aspirational at an eatery that doesn’t offer traditional table service.

On the other hand, the staff was helpful, the food came quickly. The ambiguous stick in my craw may have derived from the premature position of the tipping mechanism. All diners may agree that a 25 percent tip can emerge only as a consequence of wonderful service; the concept of a 25 percent tip before the meal, when you have no idea whether the service’ll be good or bad, is frankly ludicrous. I spent the rest of the evening trying to establish a justification for a universal tipping standard at fast-casual restaurants – like the 20-percent postprandial standard for table service – a stimulating process that ultimately made my dining experience – if not the eating itself – more enjoyable.