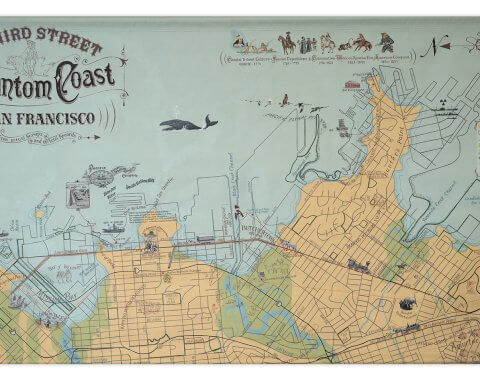

In 2016 San Francisco hosted Super Bowl 50. Then Mayor Ed Lee ordered the San Francisco Police Department to move those living on the streets from places they might be seen by tourists. Many were told to go to 13th Street — Division Street — a place of perpetual half-darkness roofed by the Central Freeway.

“So, I went down to 13th Street and there must have been three to four hundred tents, and a like number of journalists,” said Robert Gumpert, photographer and author of the recently published, Division Street. “So, I started photographing and talking to people.”

Originally from Los Angeles, Gumpert spent time in New York, Chicago and Bangkok before he and his wife, Sandy Cate, moved to Potrero Hill in 1983. He settled into working as a social documentarian, photographing the world with an eye to the social and political aspects of people, places and things.

![On one end [Division Street] dead ends into the heart of new tech and startups. And all these people were living on that street with nothing. And so, I thought, well this pretty much sums it up.](https://149352639.v2.pressablecdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/PotreroView_2022-06_Division4-e1655864472199.png)

“At some point I stopped working for the [news]papers because I couldn’t make a living at it. I got offered a contract to do photos for the Department of Industrial Relations for the state,” capturing images to decorate offices, used as part of training modules and to illustrate publications. “Then the governor changed and with it the commitment to taking pictures of workers changed.”

In 2004 he contracted with Labor Management Partnership, a collaboration between Kaiser Permanente, the Coalition of Kaiser Permanente Unions and the Alliance of Health Care Unions that works to improve labor-management relations. He stayed for ten years before it became “pretty PR-ish, which I’m not good at, in the sense that it makes me cringe.”

Simultaneously, Gumpert embarked upon self-funded projects. Starting in 1994 he spent five years following beat cops, homicide detectives, and a public defender, culminating in exhibits at the Photographer’s Gallery in London, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, and City Hall. He spent the next half-decade capturing images related to Alameda County Emergency Health Care, photographing emergency rooms and paramedics, which were also exhibited. After a year on the San Francisco Pacific Exchange’s trading floor and another in the State Legislature, working on a project called “Making Law” — “A total failure,” — Gumpert moved on to the jails.

After documenting the last three months of San Francisco’s “Old Bruno” jail in 2006 as part of the “Lost Promise” series, Gumpert continued to spend time at the County jail pursuing a project he titled “Take A Picture, Tell A Story.”

“Which was just that,” he said. “I went in, I sat down, anybody who wanted to do it would come in, I’d take a portrait, they’d tell me a story, they got copies, and I got the story and that was that.” The work was featured in several publications and exhibits, including HOST Gallery in London, “but the real worth of the project was what the prisoners seemed to get out of the process.”

Gumpert spent almost 14 years documenting inmates at San Francisco jail facilities, including the women’s jail, the San Bruno complex and the Annex, until he was thrown out in December 2019.

“Let’s just say that it is my belief that the wrong people become law enforcement,” he said. “If you want to avoid all these issues, hiring people who want to be soldiers fighting in a war is not the right idea.”

“When I left Kaiser, I really didn’t feel like I knew how to take pictures anymore,” said Gumpert. “So, I just started walking around, without knowing I needed a new project or what that would be.”

By 2016 Gumpert noticed that the number of people living on the street was increasing, with worsening conditions.

“I would stop and talk to people, especially since a lot of them were people I knew from the jail. I’d stop and talk, they would want photos,” he said. “If they’re even recognized, they’re disposable.”

Shortly before the Super Bowl, “I was standing on some street corner, and I looked down and it said, ‘Division Street.’ On one end it dead ends into the heart of new tech and startups. And all these people were living on that street with nothing. And so, I thought, well this pretty much sums it up.”

With some trepidation Gumpert began photographing encampments. His previous work in the jails prepared him to approach his new subjects.

“I was pretty aware that people will respond in a way they perceive you responding to them,” he said. “I say hello, I ask how you’re doin’, it’s easy because I am interested, I show an interest, I explain what I’m doing, and I listen to what they say. If I see somebody and I say hello and they don’t seem like they want to interact, I keep walking. I treat them like I would want to be treated. And so that means there’s a certain amount of ‘Don’t step in my space,’ ‘I don’t feel good today, leave me alone,’ or ‘Yeah, I’m happy to see you.’ Essentially, we’re all kind of the same. They just have, for whatever reason, these other issues.”

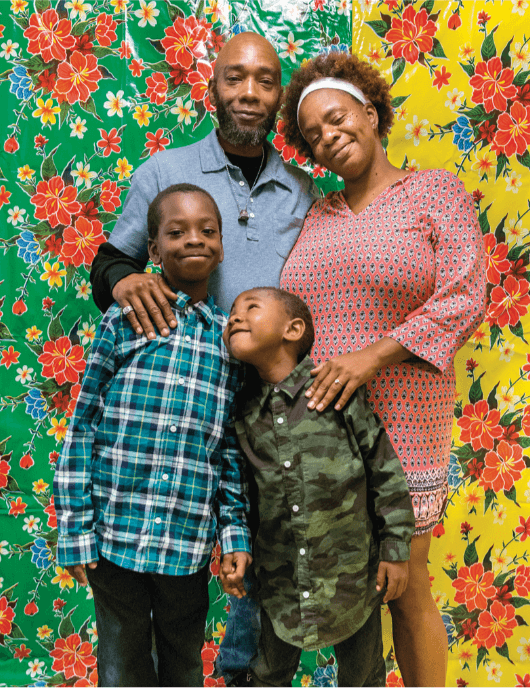

Over the six years working on the project Gumpert observed how those without permanent shelter band together.

“Somebody will set up an encampment with others or friends, and it means they can conduct business: making meetings, washing clothes, getting some food, taking the dog to the vet, whatever it is they need to do, and not be afraid their belongings are going to be stolen,” he said. “So, there’ll be somebody left in charge and that’s a rotating basis.”

Encampment residents work together. One occupant may cook; another knows how to access electricity.

“The community is really important,” Gumpert said. “It helps people stay relatively stable because there is friendship, and a support network.”

Residents can collectively ask people to leave or invite people in. The community also polices itself.

“I asked one of the guys what happens when you have a dispute,” Gumpert said. “He basically said, ‘we take care of it ourselves because if we call the police, most of us have warrants. If we call the police because somebody stole from us, they’ll come and arrest us.”

While Gumpert acknowledged street living can be a violent environment, the resulting communities provide some consistency. The groupings don’t last long, however, due to regular sanitation sweeps.

“Often when you’re swept you lose your drugs, your prescription, your social security identification, you lose all your IDs for whatever services you’re getting,” said Gumpert. “If you’ve gone down to the Linkage Center, a place where everybody is going to be given a place to live but you have to register, you have to show you’re registered, it’s how you get services; you lose all that. Then you have to spend x number of days acquiring a new tent, new sleeping gear, new clothes, and new ID, new drugs…Why is the City doing that? Sometimes I’ll talk to three or four or five people. Sometimes it’s none. Sometimes I just can’t go out.”

He made photographs, collected stories, and identified text throughout San Francisco, in the form of graffiti, bus stop ads and street signs.

“I use the text to set the story arc, the narrative,” he said. “I put [the text] on cards, then put the cards on the wall under themes, rearrange them, throw them out until I have what, maybe only shows up to me, is a narrative. You have to think about the photos that help that story arc move along, but you also have to think about how those photos relate to each other. And that’s the hardest part.”

Division Street, published by Dewi Lewis Publishing, is split into two sections. The first illustrates the way most people observe those without permanent shelter; the second illuminates their personal stories.

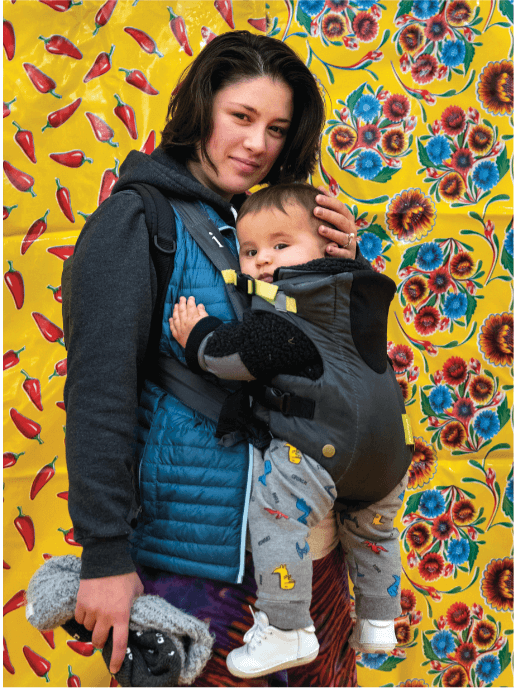

“The focus for me was people living in a town of immense wealth who have nothing,” said Gumpert. “How does that work? Why does it happen? The book doesn’t give why it happens or what to do about it. I have lots of half-baked ideas and I’m in no position to have to worry about implementing any of them. But a city with the kind of budget it has, specifically for homelessness, should not have this issue on the street.”

“If you give a set of socks, which I do, it gives them a moment of brightness. The fact I’m sitting down with them, taking a decent picture and listening to their story and showing some interest in their lives. People seem to be overwhelmed that somebody would do that. For me, that’s a terrible indictment of the society we’re living in if that’s all it takes. And there’s so few people that take that minimal step.”

Gumpert hopes those who read his book realize “the folks on the street are human, just like them, have the same concerns, the same issues, that they’re leading a hard life and they aren’t uniformly dangerous. I long since have stopped believing photos are gonna change the world, but I would consider it a success if people looked at the book and thought ‘maybe I should rethink this a bit.’”

Photo (top): from Division Street: San Francisco Giants’ fans cross the Lefty O’Doul Bridge on the way to the ballpark. 10 October 2016. Photo © Robert Gumper