I had a vision, or perhaps it was a dream, of my death. I was sitting by myself on a Northern California cliff overlooking the Pacific Ocean. The place was vaguely familiar, reminiscent of the Marin Headlands. I’d scrambled down a steep slope to settle onto a flat perch with a view of forever.

Time passed. The tide rose; splashes of saltwater licked my face. I needed to leave. I tried to scramble back up, but discovered, to my surprise, that my strength had ebbed. I scanned the cliff face but could identify no tractable escape route. After a few more panicked attempts during which neither by legs nor hands could gain purchase on the crumbly rocks, I gave up, sat back down, and watched the waves as they came closer, higher, lapping at my feet, rising. I wasn’t cold. I wasn’t afraid. I breathed deeply, slowly, and before too long was swallowed.

At 61-years-old I don’t expect to die soon, though death feels much closer than even a few years ago. Still, I take strange comfort in my vision. It’s like a prayer, a recurrent visualization that reduces my fear of the inescapable end.

Earlier this year my wife, Debbie, daughter, Sara, and I had the privilege to travel to Argentine Patagonia. After an overnight in Buenos Aires, we arrived in El Chaton, a modest town bordering Chile that serves as a staging ground for trekking in Los Glaciares National Park. After consulting with a guide, we decided to hike the Cuadrado Pass, a 22-kilometer trail rising 1,200-meters that’s largely covered with scree. The last bit could require crampons to traverse a snow field and rope to negotiate a vertical boulder field.

The guide warned us that the hike was quite challenging; she even checked the quality of our hiking boots to see if our equipment reflected the needed abilities. But Sara had spent almost two months backpacking Big Bend National Park at the start of the pandemic. I bloviated that we came from a city of steep hills, and miscalculated the kilometer to miles conversion, shortening the trek by 20 percent. It was decided; we’d depart with two guides, German and Gabriel, at 5:30 a.m. the next day.

The first several kilometers meandered through the Lenga Forest alongside a fast-running river, in which we could dip our bottles to collect clear, clean, glacier water, a rare treat. We rested briefly at the Piedra del Fraile campsite before beginning our upward journey to what was reputed to be a breathtaking view of Fitz Roy, Aguja Pollone and Paso Marconi.

The trail was unlike anything I’d encountered during other challenging hikes in Ethiopia, Peru, Tanzania, and the United States, full of rocks and loose gravel, reflecting little maintenance. Still, I bolted ahead of Debbie and Sara, trying to keep pace with our lead guide, Gabriel, who seemed to float over the slippery-steep terrain.

Roughly four-fifths of the way, as we rested next to a large boulder, Debbie and Sara decided to call it quits. They’d return to the hotel with German; I’d continue with Gabriel.

The trail didn’t get any easier, with the path increasingly no more than shallow scrims of rubble. We trudged through snow, past a gorgeous glacier lake, arriving at our final ascent: a steep snowfield leading to an even sharper boulder patch. Gabriel explained that we’d be roped together, in case one of us fell into a crevice and needed to be pulled out.

“Quite often people hiking alone fall in and aren’t found until a year later,” he said.

I was tired, with a kind of weary fogginess completely foreign to my younger self. And I was scared, with a rising anxiety I’d occasionally felt when I was on the precipice of diving to great depths, climbing at high altitudes, or skiing beyond my skill level. My death vision popped into my mind. I considered whether this was where my strength would fail.

“I’m not sure I have enough energy to do this, and get back down,” I said.

“Okay,” responded Gabriel, who continued to unpack his crampons and rope, steadily preparing for the climb. I sat down and stared up at the snowfield.

“Let me show you how to put on your crampons,” said Gabriel.

With that it was decided.

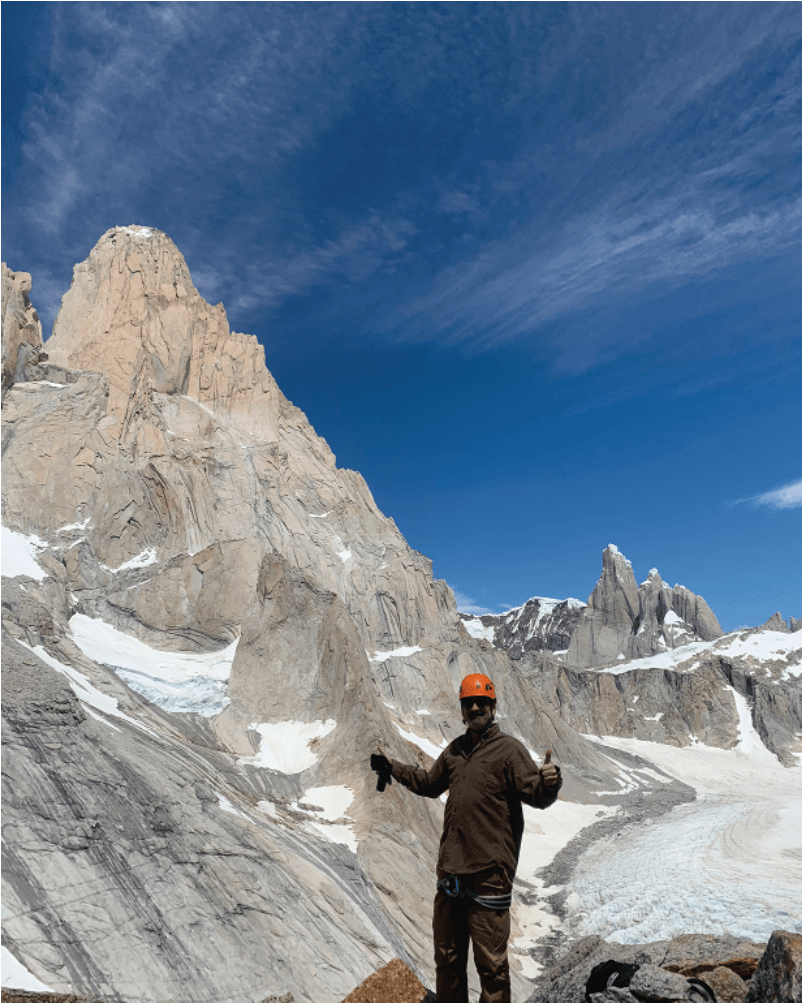

Traversing the snowfield was hard, but if I mostly kept my eyes on my feet quite doable. I gained confidence. Bouldering was easier than scrambling through scree. Before long we made it to the top.

The view was indeed mind blowing.

A couple decades ago I purchased a black t-shirt with an image of a dancing skeleton. I was in a Joseph Campbell “life is sorrow” period, leavened with a fascination with Kali, the Hindu goddess of time, doomsday and death. To me the t-shirt held a beautiful message: we’re all going to die, the essential knowledge of which should, perhaps perversely, give joy.

I rarely sported the shirt, preferring to keep it as a closeted piece of art. Once I wore it at a Burning Man Decompression Party, during which I was approached by a young woman who complemented me on it, asked where I got it, and strolled away. I was convinced that she thought I was an undercover cop, attracted not by my attire but my generally square look, which over the years had periodically prompted people in music clubs to ask about my possible affiliation with the police.

Later, I wore the shirt at Burning Man. One of my campmates, who had recently lost a loved one, found it intensely appealing, repeatedly praising it, and inquiring where it was purchased, which I’d long forgotten. As she tearfully mourned her losses at the temple, a structure that fostered deep emotions, she stared longingly at my shirt. I took it off and handed it to her.

“You need this more than I do,” I said. She hugged me fiercely.

I still mourn the loss of the shirt, odd, given its message.

I do not want to die. I know that I will. And when I do, I pray that, if I can’t dance, I’ll at least have a good view.