The road to racial equality will continue to be long and difficult. To get where most of us want to go we’ll need to learn how to (re)see things with fresh eyes, become much more mindful of our actions, and make considerable sacrifices. The alternative to taking this journey, though, is to live in an ever-worsening world, in which deepening disparities trigger increasingly frequent swells of suffering.

It’s essential to find ways to fully see one another, our collective and personal histories, and potential futures. As Adam Hochschild writes in King Leopold’s Ghost, “…the world we live in – its divisions and conflicts, its widening gap between rich and poor, its seemingly inexplicable outbursts of violence – is shaped far less by what we celebrate and mythologize than by the painful events we try to forget.”

We’re surrounded by incomplete and misleading markers and messages. In the San Francisco Bay Area, Fort Funston is named after General Frederick Funston, who while serving in the Philippines, lynched Filipinos. Andrew Jackson, memorialized on parks, streets and squares, as well as currency, championed the Indian Removal Act and enslaved hundreds of people.

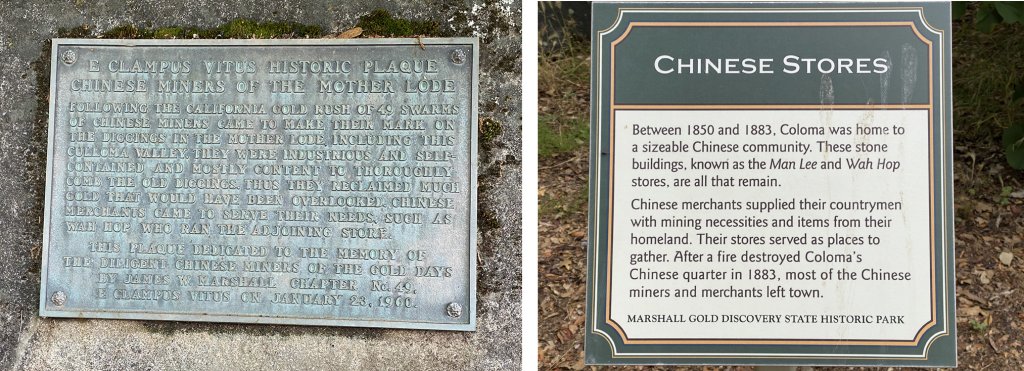

Whitewashing is everywhere, splashed across all oppressed peoples. In Coloma, California a plaque installed in 1960 in front of two structures states,

Chinese Miners of the Mother Lode

Following the California Gold Rush of ‘49 swarms of Chinese miners came to make their mark on the diggings in the Mother Lode, including this Culloma Valley. They were industrious and self-contained and mostly content to thoroughly comb the old diggings. Thus, they reclaimed much gold that would have been overlooked. Chinese merchants came to serve their needs, such as Wah Hop who ran the adjoining store.

More recent signage slightly changes the narrative,

Chinese Stores

Between 1850 and 1883, Coloma was home to a sizeable Chinese community. These stone buildings, known as the Man Lee and Wah Hop stores, are all that remain. Chinese merchants supplied their countrymen with mining necessities and items from their homeland. Their stores served as places to gather. After a fire destroyed Coloma’s Chinese quarter in 1883, most of the Chinese miners and merchants left town.

At a nearby museum a volunteer historian noted that upwards of 40 percent of the population of California’s foothills was of Chinese ancestry in 1860, a proportion that’d shriveled by two-thirds by the turn of the 20th Century. “The gold played out and they migrated to the cities for economic opportunity,” the historian said. After a long pause continuing, “Plus, people had to blame someone when everything dried up. That someone was the Chinese…” What caused the fire that “destroyed” the “Chinese quarter” remains unrecorded.

First, we must see, then we must pay attention. Elsewhere in Coloma, a placard posted in front of a large rock pocked with circular holes, mortars to pound acorns, states,

We ask visitors to please stay off the rock out of respect for its importance to the Nisenan people’s heritage…Grandmother Rock…Our people say this rock is as old as time, and if you know how to listen, she would speak of how the Earth was formed…

Yet, recently, a family – mom, grandmother, two blonde-haired girls, perhaps three and six – could be seen jumping on the rock, the adults admonishing the children not to get too close to its edge, lest they fall. It’s unlikely that same family would play tag between church pews or leapfrog in a graveyard. How often do each of us stomp across, unaware or because we just don’t care, someone’s else’s sacred place?

Harder to hide is the devastation that continues to be visited upon specific racial groups. African Americans can expect to live three and a half years less than European Americans. Infant mortality rates for African and Native Americans are twice that of European Americans. Of the nation’s 1.4 million incarcerated people, roughly 795,000 are African American or Hispanic. Black and Brown people, representing 32 percent of the population, account for 57 percent of America’s prisoners.

Over their lifetimes about one in every 1,000 Black men can expect to be killed by police. African and Native Americans, as well as Latino men, are significantly more likely than European Americans to be slain.

In Theory of Justice philosopher John Rawls posits that equality can be defined by answering the question, from the perspective of humans’ “original position,” “what terms of cooperation would free and equal citizens agree to under fair conditions?” A key feature of the original position is what Rawls’ calls the “veil of ignorance,” which prevents arbitrary facts about individuals, such as their race, from influencing peoples’ opinions about the fair characteristics of a democratically determined social compact. The veil blinds us to details that’re irrelevant to determining principles of justice, and screens out information about current cultural norms, so as to provide a transparent view of what a just society should look like.

Said differently, we can determine if we live in a just society by considering, as we metaphorically float in the sky before we’re born, whether we’d choose to be part of one racial group or another, because of the advantages or disadvantages it provides. Setting aside purely personal preferences, if we shy away from any particular people from fear, prejudice, or the pernicious outcomes more likely to be visited on that demographic, we fail this test.

It’s in our power to do better. District 10 Supervisor Shamann Walton has called for reparations to be paid to descendants of enslaved people, a damages payment for past wrongs. Perhaps such compensation could be tied to a new kind of “misery index,” which tracks racial differences in health and injustice and focuses investments, paid for by a tax on inheritances, to improved index outcomes over time. We’ll know we’ve reached a just society when no race or gender, demographic group or geography, faces a significantly worse index than another. We can’t wait.