Residents of southeastern neighborhoods are frustrated by chronic municipal neglect of unaccepted streets, public right-of-ways also known as “dirt” or “paper” roads. These pathways may be narrow, have rough surfaces, and lack sidewalks or curbs.

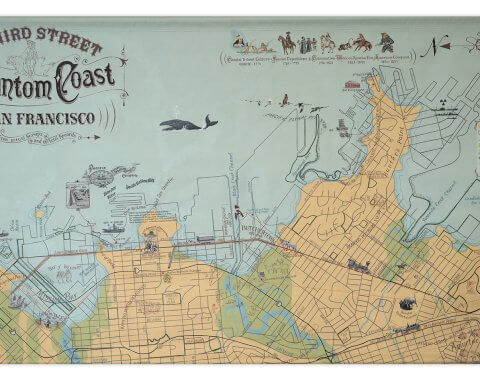

Unaccepted streets were created in the 19th Century when San Francisco was first occupied by European-Americans. Property owners would submit building plans to the City, some of which were unrealistic. Streets that existed on paper were never built, due to an impeding hill or waterway. In some cases, roads were developed, but not to code. This collection of lands defaulted into becoming public right-of-ways.

In 1997, the City audited and graded about 30,000 streets. Roughly 2,000 were left behind, unaccepted, because they didn’t meet municipal standards, such as being 26 feet wide curb to curb. San Francisco Public Works took jurisdiction over these right-of-ways.

Unaccepted streets take a wide range of forms, including dead ends following an accepted street and rocky hillsides. Under state and local law, a property owner adjacent to an unaccepted street is responsible for maintaining it to the center of the right of way, according to Rachel Gordon, San Francisco Public Works spokesperson. The City is prohibited from using general funds or state gas tax money to cover this obligation. Public Works doesn’t monitor upkeep efforts on unaccepted streets.

“We only are aware of specific instances in which maintenance is not done and we receive a service request complaint about it. Then we address those concerns on a case-by-case basis,” said Gordon.

Unaccepted streets may be beset with potholes, cracks, and trash. Unlimited parking is available on some, a boon or blight, depending on one’s perspective.

The City’s long list of unaccepted streets includes a segment of Bryant Street near Bayside Village, from roughly street addresses 367 to 0 and a portion of Delancey Street near the Bryant Street overpass, about at street address 0, as indicated in a 2023 Public Works map.

According to Katherine Doumani, Dogpatch Neighborhood Association (DNA) president, the lower portion of 20th Street at roughly the 800 block is the community’s most problematic unaccepted street. It’s well traveled by bicyclists and pedestrians, but isn’t adequately paved, with both street sides used for parking.

“The next would probably be Pennsylvania Avenue, from roughly addresses 0 to 184, north of Mariposa Street. It is a main bike route in and out of Dogpatch to 17th Street and Seventh Street,” said Doumani.

This section of Pennsylvania Avenue is poorly paved, with parking on both sides of the street.

Donovan Lacy, DNA vice president and co-chair of The Potrero Boosters and DNA joint Livable Streets Committee, is concerned that the southeastern neighborhoods have many more unaccepted streets than other parts of San Francisco.

“For too long, we’ve let these languish. For a city that has as much money as we do, it’s a concern. All City streets should be maintained to a certain level. These are not,” said Lacy.

It can take time and advocacy effort to get an unaccepted street accepted and maintained by Public Works, said Alice Rogers, president of South Beach|Rincon|Mission Bay Neighborhood Association (SBRMBNA). According to Rogers, South Beach is among San Francisco’s densest populated area, with a plethora of poorly maintained unaccepted streets.

“In Mission Bay, the issue is equally acute for the newly constructed roadways and parks. It can take more than a year for the redeveloped public amenities to be accepted and opened to the public for use,” said Rogers.

If a paper road isn’t sufficiently improved to become a standard street, community groups or developers can advocate for it to be utilized as a staircase, pedestrian pathway, or other purpose.

“These streets could become green spaces for public use,” said Tom Radulovich, director of planning and policy for the nonprofit Livable City. “That would enhance the quality of life in the City. Currently, there’s a big disincentive for property owners next to unaccepted streets to get involved. This is because they have to assume liability for improvements. Public Works will repave an unaccepted street and clean trash off it one year and not the next. There seems to be no schedule. There could be a regular schedule and notifications for neighbors who want to help.”

“Neighbors who have concerns regarding illegal dumping can contact Public Works or call 311,” said Jennifer Friedenbach, San Francisco Coalition on Homelessness executive director. “Concerns about unhoused people…should contact the San Francisco Homeless Outreach Team of the San Francisco Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing. They can connect folks with services and work on trash removal.”

“SFPA is available as a guide and fiscal sponsor to assist residents with applying for grants and figuring out solutions for unaccepted streets,” Kearstin Krehbiel, chief strategy officer for San Francisco Parks Alliance (SFPA), which acts as a fiscal sponsor for organizations that want to maintain or improve public spaces. “We’re here to imagine with residents what could be possible. Ideas include informal gardens, natural areas, walking paths, and vantage points.”

SFPA has worked with residents to improve unaccepted streets in South-of-Market, Bayview-Hunters Point, and Potrero Hill, among other neighborhoods. SFPA fiscally sponsors the De Haro Street Community Project, a group of neighbors improving the median that divides upper and lower De Haro Street on the 1300 block. This entire block of De Haro Street is unaccepted.

In 2022, the De Haro Street Community Project received a $150,000 Community Challenge Urban Watershed Stewardship Grant from the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission (SFPUC) to mitigate erosion and runoff on lower De Haro Street. The group has applied for a second grant to finish the project, monies from which could also help address concerns on upper De Haro Street.

“Upper De Haro Street is falling into the median and there is not a guardrail for cars,” said Katie Cariffe, a De Haro Street Community Project member.

Cariffe said neighbors would prefer to remove the pavement in the path and build a solid retaining wall to prevent traffic accidents. This would be expensive because mitigation would be needed to prevent naturally occurring asbestos in serpentine rocks from rising up in dust clouds. Asbestos has the potential to endanger residents and pedestrians.

The De Haro Street Community Project will use funds from the first SFPUC grant to build a living wall, as well as a gravel bioswale – a channel to concentrate and convey stormwater runoff – and infiltration planter; a water retention area filled with grasses to clean and detain runoff by allowing water to soak into the surrounding soil.

Residents can learn more about requirements for accepted streets and steps to get a street accepted at: https://sfpublicworks.org/services/acceptance.