The Radiance, a 99-unit condominium building with entrances at 330 Mission Bay Boulevard and 325 China Basin Street, is suing the City for damages caused by subsidence, or sinking. The Radiance Owners Association (ROA) represents the interests of individual condominium owners and oversees common areas, such as sidewalks.

Subsidence has been causing problems for years in Mission Bay, most notably along Third Street, where sidewalks have visibly separated from buildings. The issues identified in ROA’s suit, which seeks class-action relief on behalf of all Mission Bay residents, goes beyond sidewalks to the invisible infrastructure underneath buildings.

According to Daniel Rottinghaus, a lawyer representing the Association, the Bay mud underneath the building is slipping away and pulling with it pipes that go down before turning to run lateral to the street and connect with the sewer.

“As a result of them breaking away,” Rottinghaus said, “you basically have this sludge that is leaking out beneath the building and attracting flies.”

A soils report for the area surrounding the Radiance indicates that as much as 24 inches of settlement could occur over the next 50 years, at the rate of half an inch annually. The subsidence that’s occurred has already greatly exceeded that rate, sinking as much as 18 inches in some areas.

While subsidence is a natural process that occurs throughout the world, studies indicate that it historically occurs at a faster pace in coastal regions like the Bay Area.

Municipal officials maintain that it’s up to property owners to fix sidewalks, issuing violations to repair damages as recently as June 30, though homeowners don’t have the right to make significant changes to the paths and streets that front their properties.

Rottinghaus acknowledges that California law requires property owners to preserve the sidewalk in front of their house despite not owning it, but claims the suit addresses a completely different situation.

“This is not a problem that starts at the surface, it’s underneath the surface,” Rottinghaus said. “You can’t go out there and core into this asphalt and see what’s going on with the soil below, because you don’t own it.”

The legal action raises the larger question of whether it makes sense to build on bay fill in the first place.

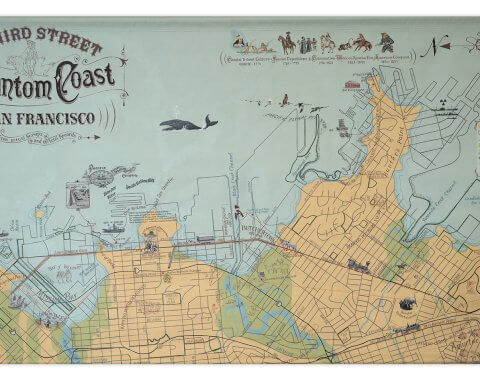

“It’s not really a great place to build for multiple reasons, not just because of subsidence but because of climate change and sea level rise,” said Joel Pomerantz, San Francisco cartographer and natural history educator. “And it’s economically dubious for the long term.”

It’s also not ecologically sound.

“We know now that the areas that were filled in were extremely important to the entire Pacific basin,” said Pomerantz. “Areas that were considered wasted space were doing a really important ecological service for humanity and all other species.”

The 303 acres of Mission Bay were developed to include more than 6,000 housing units, in excess of four million square feet of commercial space, the University of California, San Francisco’s research campus and medical center, and community-serving spaces like fire and police stations, a public school, and parks. In addition, more than $700 million in public infrastructure was installed, including streets, sidewalks, and storm drains.

As Pomerantz pointed out, the ones who “get stuck holding the bag” for paying to repair this infrastructure didn’t create the problem in the first place. Developers and the City are making money filling in the bay from increased revenue and taxes without facing the consequences.

According to Gray Brechin, historical geographer and author of Imperial City, developers realized the consequences of constructing on filled ground in 1868 after the Hayward earthquake created tremendous damage.

“They began to learn that building on fill areas is pretty stupid,” Brechin said. “But that didn’t stop them from continuing to do so because there was money to be made.”

Rather than not constructing in the area, Rottinghaus thinks it should be properly maintained by the City, with associated costs not pushed off onto the residents.

“Maybe what’s necessary in this area is a funding mechanism to constantly do upgrades so that people don’t trip and fall,” he said. “You can’t lay that off onto the people. You can’t say we’re going to have you maintain the infrastructure of your city.